As with commercial poultry production, infectious diseases in backyard poultry flocks are common and costly problems. Although the same infectious agents affect all poultry, in a backyard setting some diseases are more common or particularly concerning because of predominant management styles. Furthermore, certain management considerations are especially important for backyard poultry, given that the scale, economics, and goals of production are vastly different from those of commercial flocks.

Parasitism in Backyard Poultry

As with other bird species, the common parasites in poultry are mites, lice, ticks, worms, and protozoa.

Two common mites of poultry are the northern fowl mite (Ornithonyssus sylviarum) and the red mite (Dermanyssus gallinae; see northern fowl and poultry red mites image). The northern fowl mite is usually found around the vent, tail, and breast (see Ornithonysuss sylviarum mites and northern fowl mites in vent region images). These mites are easily observed as small, reddish-brown flecks.

Red mites feed only at night, making daytime diagnosis difficult (see poultry red mite and northern fowl and poultry red mites image images). They can be found in cracks and seams near bedding areas and look like flea dust or salt and pepper–like deposits. Red mites cause feather loss, irritation, and anemia.

Several types of lice live on poultry, and lice or nits (egg packets of lice) can be observed at the base of feathers (see nit image; also see poultry louse species image). In severe infestations, growth and egg production can be affected. Insecticides are available for treatment.

Nits, hen

Image

Courtesy of Dr. Yuko Sato.

Fowl ticks comprise a group of soft ticks that parasitize many species of poultry and wild birds. Ticks in poultry are easily missed, because they spend relatively little time on the bird. Heavy infestations can result in anemia or tick paralysis, and ticks can be vectors for Borrelia anserina (the bacterium that causes spirochetosis).

Application of pesticides to affected buildings is the treatment of choice. After houses are cleaned, appropriate pesticides should be applied using a high-pressure sprayer to thoroughly treat walls, ceilings, cracks, and crevices. After treatment, cracks and crevices should be filled in.

Roundworms and tapeworms are the most common internal poultry parasites (see images in Helminthiasis in Poultry) and are generally the result of soil contamination and poor management. Unless infestations are heavy, clinical signs are usually not evident. Because most domestic poultry have some internal parasitism, a fecal examination should be performed before treatment to assess the extent of infestation (and to provide a benchmark against which to monitor the effectiveness of treatment).

Treatment of internal parasite infestations in poultry is discussed elsewhere (see Helminthiasis in Poultry).

Proper litter management decreases parasite loads and reinfection.

As in commercial poultry production, in backyard poultry flocks the control of coccidia is one of the more common and costly problems. Coccidia are found primarily in the intestinal tract of most poultry; in geese they are also found in the kidney.

Coccidiosis most often occurs in birds 1–4 months old. Birds are not susceptible to infection until 10–14 days of age.

Clinical signs of coccidiosis in poultry include diarrhea that is often bloody and that frequently leads to loss in production, general malaise, and death.

Coccidia thrive in moist, heavily soiled litter, and disease often results because the density of birds is too high. Coccidiosis can be prevented by coccidiostats added to feed, which can be given to birds as early as in their starter diet. Outbreaks can be treated with selected coccidiostats and extralabel sulfa drugs. Sulfa drugs have a long withdrawal period and should not be used in laying hens.

Routine yearly fecal examinations are recommended for all backyard poultry flocks.

Vaccination against coccidiosis is available for mail-order day-old chicks from certain hatcheries. The vaccine is administered at the hatchery; care must be taken to provide ideal brooding conditions to confer protective immunity. Chickens vaccinated against coccidiosis should not be given feed medicated with coccidiostats, because coccidiostats can negate the vaccine’s effectiveness.

Consult the label before using any insecticides or antiparasitics to ensure that the product is up-to-date, labeled by the EPA, and approved for use in poultry and on poultry premises. Topical products approved for use in dogs and cats, such as fipronil and selamectin, are strictly forbidden for use in all food animals, including backyard poultry. Good resources include VetPestX, a database of registered pesticides for animals; and the Food Animal Residue Avoidance Databank (FARAD) Medications Labelled for Layers web page, which also includes information about labeled antimicrobials.

Viral Diseases in Backyard Poultry

Avian Encephalomyelitis

Avian encephalomyelitis occurs in chickens, turkeys, pheasants, and quail; it affects primarily chicks 1–3 weeks old (see clinical signs video and brain lesion image). Nearly all commercial poultry flocks are infected; however, morbidity is low because of maternal antibodies.

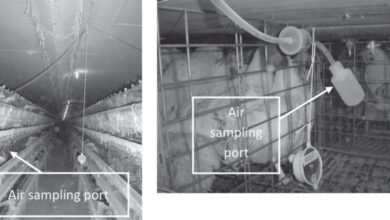

Avian encephalomyelitis can be transmitted vertically (from parent to offspring during pregnancy or the birth process) in eggs laid between 5 and 13 days after infection and is an enteric infection under natural conditions. The disease is transmitted more rapidly in floor-raised birds than in cage-raised birds.

There is no treatment for avian encephalomyelitis, and vaccination of breeders (both chickens and turkeys) is critical to prevention because it ensures passive transfer of maternal antibodies to protect the young during early life. Because many specialty breeders, particularly those who sell birds to an intermediate supplier, do not vaccinate, the disease is fairly common in backyard poultry. Birds should be vaccinated at > 8 weeks old and

uxjd1m