Rabies outbreak on a goat farm and An epidemiologic investigation in Ghana

- Overview of the Rabies Outbreak in Ghana - How the Infection Spread on the Goat Farm - Key Findings from the Epidemiologic Investigation - Role of Dogs in Rabies Transmission - Public Health and Veterinary Response - Vaccination and Control Measures Implemented - Challenges Faced During the Outbreak - Lessons Learned and Future Prevention Strategies - Importance of One Health Approach in Rabies Control - Raising Awareness and Educating Local Communities

Highlights

- •Rabies is confirmed on a goat farm in Ghana.

- •Rabies outbreak was controlled through vaccination of goats.

- •Potential human rabies was averted by vaccination of farm workers.

Abstract.

Objective

Rabies is a zoonotic viral disease that affects approximately 60,000 individuals worldwide each year. Although rabies can infect all warm-blooded animals, its occurrence in goats is relatively rare. This study investigated and reports a rabies outbreak on a goat farm in Ghana.

Design

A 10-month-old Boer goat was presented to a teaching hospital exhibiting ataxia and paddling movements, and it succumbed to the disease a day after presentation. Farm records indicated that 14 out of 57 goats had died within a month, but all were buried without laboratory testing or diagnosis. A guard dog on the farm, which consumed the carcass of one of the affected goats, died 13 days post-consumption.

Results

Brain tissues from both animals were tested for rabies using conventional reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and both tested positive for rabies infection. The outbreak was managed on the farm through the immediate administration of anti-rabies vaccinations to the remaining goats and post-exposure prophylaxis to attendants who had been exposed through handling.

Keywords

Rabies in goats

Outbreak of rabies

Guard Dogs

Ghana

Ataxia

Drooling

Introduction

Rabies is a fatal zoonotic disease affecting warm-blooded animals, including domestic and wild species. It is caused by a negative-stranded RNA virus from the Rhabdovirus family. Transmission to humans and animals primarily occurs through bites or scratches from infected animals. Livestock are predominantly infected through bites from rabid dogs, although other rabid carnivores may serve as source of infection. Worldwide, dog-mediated rabies is frequently reported, ranking 10th among infectious disease mortality causes. Dogs are responsible for up to 99 % of human rabies cases. Despite effective post-exposure prophylaxis vaccines, there are 50,000–60,000 deaths annually worldwide. According to Dodet rabies persistence in Africa may be attributed to unreliable epidemiologic data, negligence, lack of public awareness, and barriers to accessing vaccinations.

Rabid goat

Case presentation

On July 20, 2023, a 10-month-old male Boer goat was presented to the Small Animal Teaching Hospital (SATH) at the University of Ghana with paralysis. The goat was recumbent, drooling, and displayed paddling movements. According to farm management, initial symptoms observed from July 17, 2023 included ataxia, neck stretching, and a wobbly gait, which intensified the next day. Initial suspicion was directed toward floppy kid syndrome, based on previous medical history; the goats were treated accordingly, but no improvement was observed.

Farm characteristics and setting

The farm maintained a population of 57 goats, comprising African dwarf and Boer goats, predominantly imported, along with their hybrids. The farm used a zero-grazing system to prevent goats from encroaching on neighboring farms because crop farming was the primary economic activity of surrounding communities. Historical accounts indicated that the farm was in a suburb where dog rearing was culturally prohibited, allowing only cats as pets. Nevertheless, the goat farmer kept a 10-month-old local breed dog as a guard within the goat enclosure, without any vaccination history. A stray cat frequently interacted with the goats, occasionally drinking from their water troughs, in the weeks before mortality onset on the farm. Notably, the cat was no longer observed on the farm by July 9, 2023.

History of clinical signs

On July 11, 2023, a west African dwarf goat, aged 2 and a half months, was found recumbent in the pen, exhibiting unusual and continuous bleating. This condition progressed to paddling movements and persistent recumbency. The kid died 6 days after initial clinical signs. An adult goat also died, and the farm’s guard dog consumed the carcass. On July 12, 2023, a lactating hybrid doe and a west African dwarf goat showed similar symptoms and died a day after presentation. Three more goats exhibited similar symptoms and died shortly after. In total, 14 goats died with similar clinical signs, as reported by the farmer. The Boer goat presented to SATH on July 20 was screened for trypanosomiasis and other hemoparasitic infections due to the clinical signs and the farm’s location, associated with increased tsetse fly activity during the rainy season in southern Ghana (May-August). Both tests were negative, and the goat died the next day. Given the clinical manifestations, the carcass was submitted for rabies testing at the Accra Veterinary Laboratory (AVL) of the Veterinary Services Department of the Ministry of Food and Agriculture of Ghana.

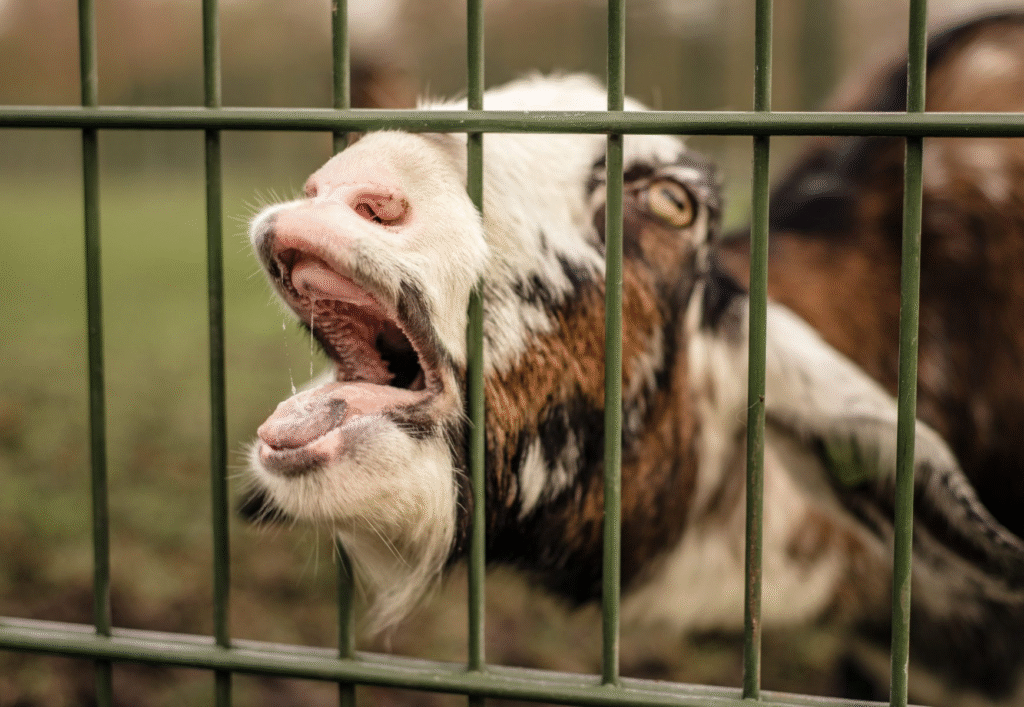

The guard dog on the farm

On July 12, 2023, the unvaccinated guard dog consumed a goat carcass. The dog then exhibited abnormal behavior, hiding and displaying aggression toward the goats. Following advice, the farmhand quarantined the dog. It succumbed 13 days later, on July 25, 2023 and was interred without investigation. On July 26, 2023, the dog was exhumed for rabies testing, as recommended by the SATH and AVL team investigating farm mortalities.

Laboratory investigation

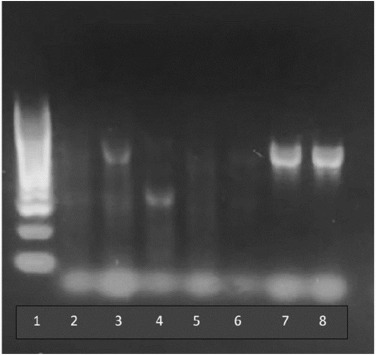

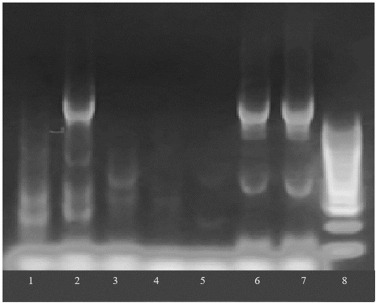

The goat and dog specimens were submitted to AVL on July 21 and 26, 2023. Various brain tissue sections, including the cerebellum and brain stem, were extracted for diagnostics. The Qiagen One-step reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, using primer set (G5A and G3-STP) to amplify the glycoprotein, detected viral RNA in both samples. Amplifications were conducted with a Bio-Rad Thermal Cycler. Denaturation was at 50 °C for 30 min, followed by 95 °C for 15 min. Reactions underwent 35 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a final elongation at 72 °C for 5 min, with samples maintained at 12 °C. A 5-µl aliquot of reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction amplification was analyzed via gel electrophoresis on 1.2 % agarose gels, using a standard visualization procedure, with an anticipated band size of 652 bp, as depicted.

Image of gel from caprine sample from the goat farm in a suburb of Cape Coast. 1: ladder (100 bp), 2: no template, 3: goat brain tissue, 4: goat brain tissue, 5 and 6: negative control, 7 and 8: positive control.

Image of gel from the canine sample from the goat farm in a suburb of Cape Coast, Ghana. 1, 2, 3: Dog brain tissue, 4, 5: negative control, 6, 7: positive control, 8: ladder (100 bp).

Actions taken post investigation

A veterinary team vaccinated the remaining 42 goats in the pen. Each goat received a single 2-ml dose of Defensor rabies vaccine (Zoetis, South Africa), recommended for dogs, cats, and ruminants. Farm workers were recommended for rabies post-exposure vaccination. Mass rabies vaccination was recommended for cats in the affected community.

Discussion

Rabies caused neurologic symptoms and mortality in a goat farm near Cape Coast, Ghana. The outbreak may have been mediated by a cat, as the guard dog died after consuming a potentially rabid goat carcass. A 7-year analysis of secondary rabies data in Ghana showed 91 % of rabid animal cases involved dogs and 4 % cats, highlighting dogs’ role in rabies transmission. However, goat mortality began at least 7 days before behavioral changes in the guard dog. Although the incubation period for paralytic rabies in goats is shorter (2–8 days) than in unvaccinated dogs (19–38 days), the dog was unlikely the disease source. Evidence suggested the dog exhibited behavioral changes after consuming a potentially rabid goat carcass, aligning with documented rabies transmission through buccal mucosa exposure. The dog died 13 days after quarantine, yet goat fatalities continued, resulting in a 25 % loss of the total stock of 57, all showing neurologic symptoms before death. The community prohibited dog ownership, making disease introduction by another dog unlikely. Although the health status of a stray cat that interacted with the goats before the outbreak was unknown, its disappearance and subsequent goat deaths suggest a possible link between the cat and the rabies outbreak.

Through investigation, rabies was identified as the cause of mortality on the farm, leading to identification of individuals exposed to the virus who were recommended for post-exposure prophylaxis. This intervention likely prevented human fatalities. Prompt vaccination of remaining goats with rabies vaccine effectively controlled the outbreak. In regions where rabies threatens public health and animal populations, the One Health Approach is advocated. This approach emphasizes prompt post-exposure treatments, livestock vaccination, and implementation of biosecurity measures.

The investigation was limited by inability to ascertain the health status of the stray cat frequenting the goat pen before mortality onset, as well as its duration before disappearing. This hindered measurement of the disease’s incubation period on the farm.

Conclusion

Rabies was determined as the cause of mortality on the goat farm, controlled through anti-rabies vaccinations in the remaining goats. Rabies is endemic in sub-Saharan Africa and must be considered in all neurologic presentations in livestock and other species.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Summary

A rabies outbreak on a goat farm in Ghana prompted an epidemiologic investigation to determine the source, extent, and impact of the infection. The investigation revealed that the disease was likely transmitted by rabid dogs, which exposed goats and possibly humans to the virus. Authorities conducted interviews, tested animals, and reviewed vaccination records. Control measures included vaccinating livestock and pets, educating the public, and improving surveillance. The outbreak highlighted the need for better rabies prevention strategies, including regular animal vaccinations and stronger coordination between veterinary and public health sectors.