Abstract

The dromedary camel is a good source of meat especially in areas where the climate adversely affects the performance of other meat

animals. This is because of its unique physiological characteristics, including a great tolerance to high temperatures, solar radiation,

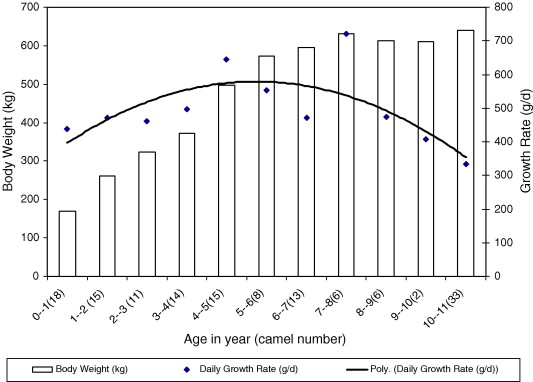

water scarcity, rough topography and poor vegetation. The average birth weight of camels is about 35 kg, but it varies widely between

regions, breeds and within the same breed. The meat producing ability of camels is limited by modest growth rates (500 g/day). However,

camels are mostly produced under traditional extensive systems on poor levels of nutrition and are mostly slaughtered at older ages after

a career in work, racing or milk production. Camels reach live weights of about 650 kg at 7–8 years of age, and produce carcass weights

ranging from 125 to 400 kg with dressing-out percentage values from 55% to 70%. Camel carcasses contain about 57% muscle, 26% bone

and 17% fat with fore halves (cranial to rib 13) significantly heavier than the hind halves. Camel lean meat contains about 78% water,

19% protein, 3% fat, and 1.2% ash with a small amount of intramuscular fat, which renders it a healthy food for humans. Camel meat has

been described as raspberry red to dark brown in colour and the fat of the camel meat is white. Camel meat is similar in taste and texture

to beef. The amino acid and mineral contents of camel meat are often higher than beef, probably due to lower intramuscular fat levels.

Recently, camel meat has been processed into burgers, patties, sausages and shawarma to add value. Future research efforts need to focus

on exploiting the potential of the camel as a source of meat through multidisplinary research into efficient production systems, and

improved meat technology and marketing.

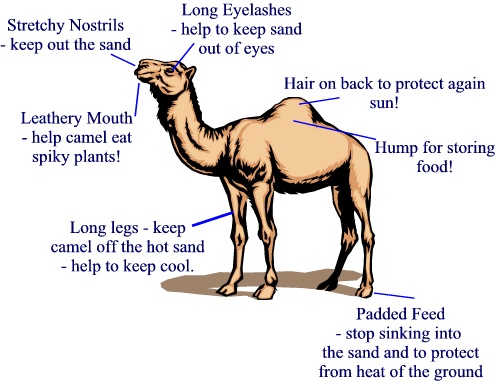

🐫 Some Fun Facts About Camels

- Camels can survive without water for up to two weeks in extreme desert heat.

- They store fat in their humps, not water — this fat gives them energy.

- A healthy camel’s hump can weigh up to 80 pounds (36 kg).

- When a camel’s hump deflates, it means it’s used up its fat reserves.

- Camels can drink up to 40 gallons (150 liters) of water in one go!

- They have three sets of eyelids and two rows of eyelashes to protect against sand.

- Camels can close their nostrils during sandstorms.

- Their feet are wide and padded, perfect for walking on hot, soft sand.

- Camels are called the “ships of the desert” because of their smooth movement over sand.

- Camels can tolerate body temperatures over 104°F (40°C) without sweating.

- They are excellent swimmers, even though they rarely encounter water.

- Camels’ blood cells are oval-shaped, which helps them flow even when dehydrated.

- There are three types of camels: Dromedary (one hump), Bactrian (two humps), and Wild Bactrian.

- Dromedaries make up about 90% of the world’s camel population.

- Camels can run up to 40 mph (65 km/h) in short bursts.

- A camel’s thick coat insulates it from both heat and cold.

- They can live for 40 to 50 years in the right conditions.

- Baby camels are born without humps, which develop as they grow.

- Camels chew cud, meaning they regurgitate and re-chew their food.

- They have split upper lips that help them grab tough desert plants.

- Camels are used for milk, meat, wool, and transport in many cultures.

- Camel milk is rich in iron, vitamin C, and low in fat compared to cow’s milk.

- Camel races are a popular sport in the Middle East, Africa, and Australia.

- Camels communicate by grunts, moans, and loud bellows.

- They can be stubborn and grumpy, but they’re highly intelligent.

- Camels can go weeks without food if needed.

- A thirsty camel can drink water so quickly it looks like it’s inhaling it.

- Camels have been domesticated for over 3,000 years.

- In cold deserts like Mongolia, Bactrian camels can survive freezing winters.

- Camels often spit when annoyed — but it’s mostly regurgitated food, not saliva!

Content

Introduction

Growth rate and live weight Carcass weight and dressing-out percentage

Non-carcass components

Carcass composition

Meat composition

Meat quality

meat quaily of camel/nutriton

Funfacts

INTRODUCTION

The family Camelidae include two subfamilies: Camelinae (Old World Camelids) and Laminae (New World

Camelids). There are two species of camel within the genus

Camelus. The Dromedary one-humped camel (Camelus

dromedaries) is most widely distributed in the hot arid

areas of the Middle East and Africa, whereas the Bacterian

two-humped camel (Camelus bacterianus) is found in parts

of central Asia and China (Dorman, 1986). Four species of

the New World camelids are found in South America: the

guanaco (Lama guanacoe) and the vicuna (Vicugna vicugna) are wild, whereas the llama (Lama glama) and the alpaca (Lama pacos) are domesticated (Murray, 1989;

Skidmore, 2005). The Llama and Alpaca are mainly used

for meat and fibre production. The camel originated in

North America and was domesticated by secondary

nomads around 4000 years ago in South Arabia primarily

for transport and labour rather than as a producer of meat,

milk or clothing (Wilson, 1984). The dromedary is more

numerous than the Bactrian camel and represents almost

90% of the genus Camelus. Generally, there has been relatively little differentiation into specialised types in the camels (Wilson, 1998). Camels are multipurpose animals with

females used primarily as milk producers, the males for

transport or draught and both sexes providing meat as tertiary product. The genetic diversity and relationships

amongst the dromedary populations are poorly documented. Phylogenetic analysis (micro-satellite loci) Llama (Skidmore, 2005).

The dromedary camel is one of the most important

domestic animals in the arid and semi arid regions as it is

equipped to produce high quality food at comparatively

low costs under extremely harsh environments (Knoess,

1977; Yagil, 1982; Yousif & Babiker, 1989). The camel

has great tolerance to high temperatures, high solar radiation and water scarcity. It can survive well on sandy terrain

with poor vegetation and may chiefly consume feeds unutilized by other domestic species (Shalah, 1983). Tandon,

Bissa, and Khanna (1988) noted that the camel is likely

to produce animal protein at a comparatively low cost in

the arid zones based on feeds and fodder that are generally

not utilized by other domestic species due to either their

size or food habits.

Growth rate and live weight

Growth in body weight is the basis of meat production in domestic animals. There are many factors that influence growth rate including breed, nutrition, sex and health.

Heredity is the main factor determining prenatal growth, either directly via the genotype of the foetus or indirectly through the genotype of the dam (Shalash, 1978). Prenatal patterns of growth and development of the camel foetus is similar to that of cattle (Musa, 1969). However, the lifetime utput of meat for breeding female camels is often limited

due to long gestations, low calving rates and long milk

feeding periods, especially under traditional systems. After

a gestation periods of 13 months, a camel female usually

bears a single calf, and rarely twins. The new born camel

walks within hours of birth, but remains close to its mother

sometimes until maturity at five years of age (Bhargava,

Sharma, & Singh, 1965).

The average birth weight of the dromedary camels is

about 35 kg (Wilson, 1978), but it varies widely between

regions, breeds and within the same breed. Reports on

camel birth weights range between 27 and 39 kg, which is

comparable with that of tropical cattle breeds. For

instance, reports of birth weights include 26–28 kg for

Somali camels (Field, 1979; Ouda, 1995; Simpkin, 1983);

27 kg for Tunisian camels (Hammadi et al., 2001) and

39 kg for Indian camels (Bissa, 1996).

The influence of sex on birth weight of the dromedary

camel appears to be minimal (Ouda, 1995). Males

(38.2 kg) were slightly but not significantly heavier than

females (37.2 kg) in the study of Yagil (1985). Harmas,

Shareha, Biala, and Abu-Shawachi (1990) also reported

average birth weights of 36 and 34 kg for male and females,

respectively with no significant differences between sexes.

No differences in body weight between sexes were observed

up to two years by Ouda, Abui, and Woie (1992) or up to

four years of age by Simpkin (1983).

camels in different countries with the lightest live weights in

Somalia desert camels (350–400 kg) and the heaviest liveweight (660 kg) in Indian camels. In Australia, the weights

of mature camels ranged from 514 to 645 kg for males and

470 to 510 kg for females. Iranian camels at an age of five

years were ranged in weight from 340 to 430 kg (Khatami,

1970). There are also reports of varying camel body

weights within the same region. Live weight in 4300 Turkman camels ranged between 439 and 489 kg (Keikin, 1976).

Nutritional history and body condition have significant

effects on live-weight. Live weights of mature well-finished

male desert Saudi camels ranged between 359 and 512 kg

with an average of 475 kg (Babiker & Yousif (1987). However, there are reports of extremely high body weights in camels.

Non-carcass components

There is little data available on non-carcass components

of the camel. Proportions of live weight as feet and hide are

higher for the camel than for cattle, but the head is proportionately lower than cattle (Mahgoub et al., 1995a, Mahgoub, Olvey, & Jeffrey, 1995b). The latter difference is

most likely due to lack of horns in the camel. The head,

hide and feet contributed 2.4%, 7.3% and 3.4% of live

weight in the dromedary camels evaluated by Herrman &

Fischer (2004). Proportions of offal (edible non-carcass

components) are high in the camel (Table 2) and therefore,

they represent a very useful protein source in arid areas

where the camel is mainly kept for meat. The relative proportions of body components indicated that the heaviest

component was the hide followed by intestines while the

lightest organ was the spleen followed by reproductive

organs (Yousif & Babiker (1989). The liver weight was

lighter than values for Somali camel livers reported by

Congiu (1953). The weights of head, liver, feet, hide and

gut fill agreed with values reported by Wilson (1978) for

the dromedary. Breed differences and the nutritional state

of the animal may be responsible for any variations

between different studies. The camel body contained an

average of about 4.2% offal (liver, heart and lungs). The

non-carcass included the head (3.5%) and the feet (3.6%)

and hide (8.6%)

Carcass composition

There is no standard cutting system for camel carcasses

as there are for other meat animal species. Abouheif et al.

(1990a) divided the carcass side into forequarter and hindquarter by cutting between the 11th and 12th ribs. The

forequarter is usually divided into five wholesale cuts

(neck, shoulder, brisket, rib and plate), while the hindquarter into three wholesale cuts (loin, flank, and leg). shows the general cutting procedures for eight wholesale

cuts. with those from a second study. The values from the two

studies are very similar. The largest cut of the carcass using

this cutting procedure is the leg followed by the shoulder.

Meat composition

Camel meat varies in composition according to breed

type, age, sex, condition and site on the carcass. Water content differs only slightly between species, while differences

in fat content are more marked (Sales, 1995). Camel meat

contains 70–77% moisture (Al-Owaimer, 2000; Al-Sheddy,

Al-Dagal, & Bazaraa, 1999; Dawood & Alkanhal, 1995;

Kadim et al., 2006). These levels are higher than those in

meat of other farm animal species (Table 8). It is also a

good source of protein containing about 20–23% (Al-Owaimer, 2000; Kadim et al., 2006; Kilgour, 1986). This level is

similar to those in other farm animals, but lower than that

in the Llama (Table 8). These protein contents are similar

to values reported by Dawood & Alkanhal (1995), but

are lower than values reported by Elgasim & Alkanhal

(1992). This level of protein in camel meat makes it a good

source of high quality protein in arid and semi-arid regions.

Chemical intramuscular fat levels in camel meat vary

greatly. Al-Owaimer (2000) reported a value of 5.2% for

camel Longissimus dorsi. Kadim et al. (2006) reported a

mean chemical fat of 6.4% for camel Longissimus dorsi,

which is comparable to the 7% reported by Dawood &

Alkanhal (1995). Shalash (1988), El-Faer, Rawdah, Attar,

& Dawson (1991), & Elgasim & Alkanhal (1992) reported.

Here’s a blog-friendly, informative overview of the meat quality of camel, ideal for your website:

🥩 Meat Quality of Camel Nutritional and Culinary Insights

Camel meat is a lesser-known but highly nutritious red meat consumed in many parts of the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. It’s becoming more popular globally for its health benefits and unique taste.

Key Qualities of Camel Meat

- Lean and Low-Fat

- Camel meat is generally leaner than beef and lamb, making it a great choice for health-conscious consumers.

- Fat content varies with age — younger camels have tenderer, leaner meat.

- High Protein Content

- Camel meat is rich in high-quality protein, essential for muscle building and repair.

- It contains 19–23% protein, similar to beef.

- Low in Cholesterol

- Studies show camel meat has lower cholesterol levels than other red meats, making it heart-friendlier.

- Rich in Minerals

- Excellent source of iron, zinc, potassium, and magnesium.

- Helps in oxygen transport, immune function, and muscle health.

- Good Fatty Acid Profile

- Contains unsaturated fatty acids, which are better for heart health compared to saturated fats in other meats.

- Distinct Taste

- The flavor of camel meat is mild and slightly gamey, often compared to beef but coarser in texture.

- Younger camels (under 3 years) provide tenderer meat, which is more palatable.

- Cooking Tips

- Best cooked slow and low (stewing, braising) to retain moisture.

- Popular dishes include camel kebabs, camel burgers, and camel curry.

- Halal-Friendly

- Camel meat is halal in Islam, making it suitable for Muslim dietary laws.

- Sustainable Protein Source

- Camels are well-adapted to harsh climates and require less water and pasture than cattle, making them a more sustainable meat source in arid regions.

- Cultural and Economic Value

- Widely consumed during special occasions in many Arab and African cultures.

- Increasingly sold in specialty meat markets and gourmet restaurants worldwide.

Final Thought

Camel meat is a nutrient-rich, eco-friendly, and flavorful alternative to conventional red meats. With growing global interest, it holds promising culinary and nutritional potential.

Here’s a clear and blog-friendly list of the main parts of a camel’s body, useful for educational or animal anatomy content on your site:

🐫Body Parts of a Camel

- Head – Contains the brain, eyes, ears, nose, and mouth.

- Eyes – Protected by long eyelashes and a third eyelid to block sand.

- Ears – Small and hairy, helping reduce sand and dust entry.

- Nostrils – Slit-like and closable to protect against sandstorms.

- Mouth – Includes tough lips that allow camels to eat thorny desert plants.

- Neck – Long and curved, helps in reaching high or low vegetation.

- Hump(s) – Stores fat, not water; energy reserve in harsh conditions.

- Back – Strong and broad, used to carry loads or riders.

- Legs – Long and powerful; ideal for walking long distances in sand.

- Feet – Wide, padded, and split-toed, preventing sinking into sand.

- Tail – Short with a tuft of hair; helps swat flies and signal moods.

- Stomach – A ruminant with multiple compartments for digesting tough desert plants.

- Heart – Large and adapted to withstand extreme dehydration.

- Lungs – Efficient at breathing in dry air with minimal moisture loss.

- Skin/Coat – Thick and insulating, protects from extreme heat and cold.

- Knees – Have calloused pads to protect while kneeling on hot sand.

- Genitals – Located near the hind legs, like other mammals.

- Udder/Teats (in females) – For feeding young; camel milk is highly nutritious.

- Teeth – Strong molars for grinding desert vegetation and cud.

- Brain – Highly adaptive; camels are known for their intelligence and memory.